The LROC QuickMap is like a web-based virtual telescope that puts thousands of terabytes of lunar imagery at your fingertips. Its powerful interface makes browsing lunar images deceptively easy—and addicting.

I’ve written about the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LROC) QuickMap tool before, but mostly on our Facebook group (like this, and this) where posts tend to quickly get lost, so I thought I’d put something here too.

The LROC QuickMap tool is part of a suite of similar tools made available by the group “Applied Coherent Technology,” a tech company that provides services to the federal government, particularly in the areas of data collection, image analysis, visualization, and publishing. NASA has used ACT extensively to assist with public-facing image availability. Quietly and without much fanfare, they have released a series of tools over the years that amateur astronomers should love – tools that deserve to be more widely known. In addition to the Lunar QuickMap discussed here, they also have similar tools for Mercury and Mars. But it’s the lunar tool I want to discuss here because it is such a powerful site to assist amateur lunar observers, or to launch a full-on obsession with lunar observing whether you have a telescope or not.

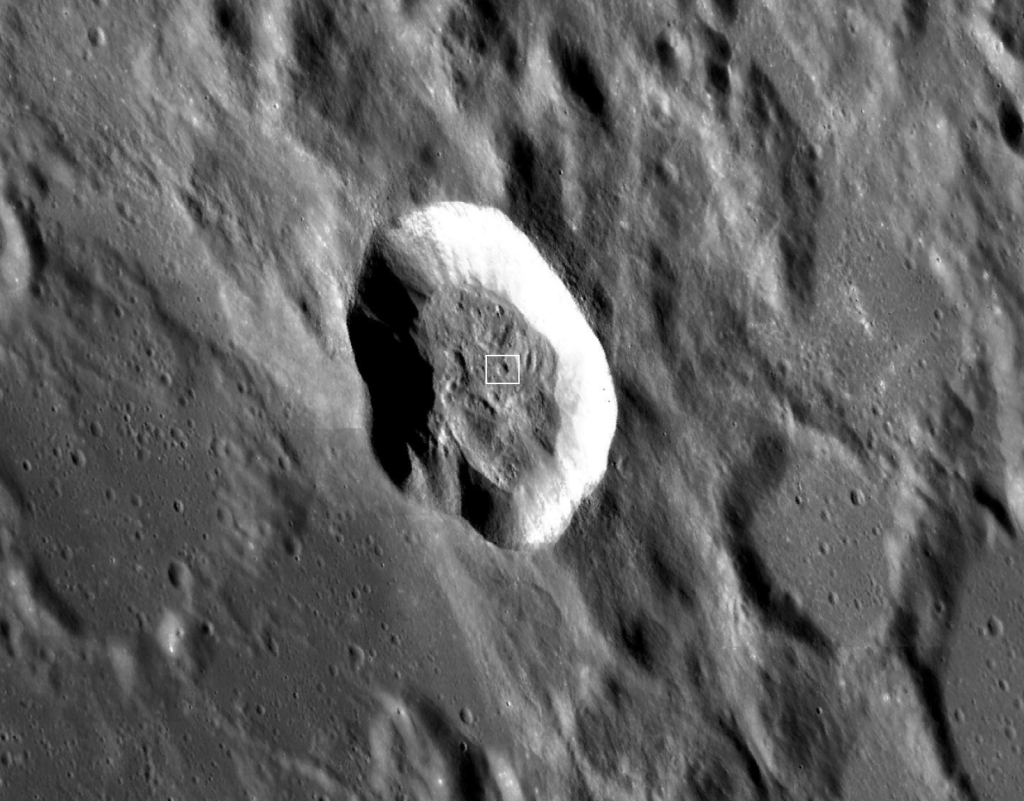

As a quick example of the power of this tool, let’s examine the magnification range available to us. The image below is a shot of a small mound of regolith inside the crater Proclus. Small hill-like features such as this are called “hummocks.”

This hummock has no name and you’ve likely never heard of Proclus either. Proclus is best known for its unusual and asymmetric system of rays best seen at high sun angles (near full moon). Those rays are nearly invisible in the images I’ve chosen here because of the lower sun angle that highlights vertical relief instead.

The hill is slightly less than a kilometer wide and probably about 100 to 200 meters high. The resolution is so good that we’re seeing rocks and boulders from building sized down to smaller than a meter. If you wanted to, you could zoom in even more and examine individual boulders. This is the type of geologic feature that would fit neatly within, for instance, Devil’s Lake State Park, and there would be a popular hiking trail to the top.

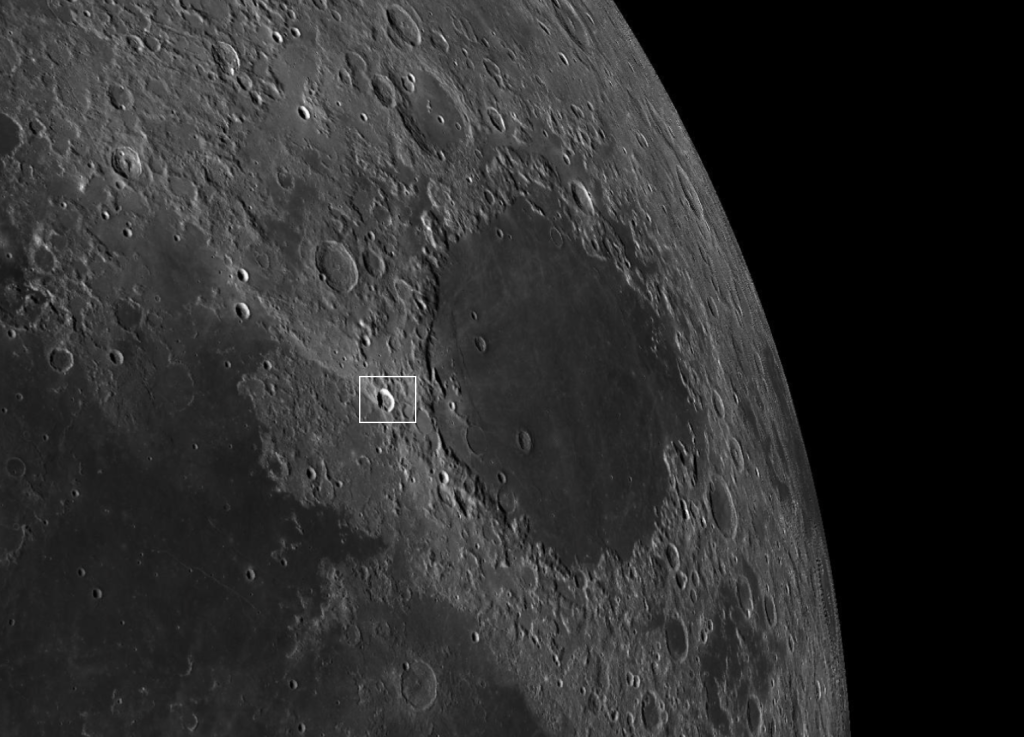

But let’s zoom out instead to look at the larger context. This hill is a small feature inside Proclus, which sits within the broader context of the lunar highlands just west of the boundary of Mare Crisium. Here’s an LROC shot of Proclus. The crater is about 27 kilometers wide along its widest dimension, roughly the same straight-line distance from downtown Madison to YRS. The floor of Proclus is a mix of hummocky, slumped terrain.

Sunlight is coming from the left in this image and brightly illuminating the eastern (rightmost) wall of the crater. Take another look at the small hummock in the white box (or in the previous image) and you see the feature more clearly as an elevated hill, illuminated on the left side and shadowed on the right, what you would expect for a hill lit from the left.

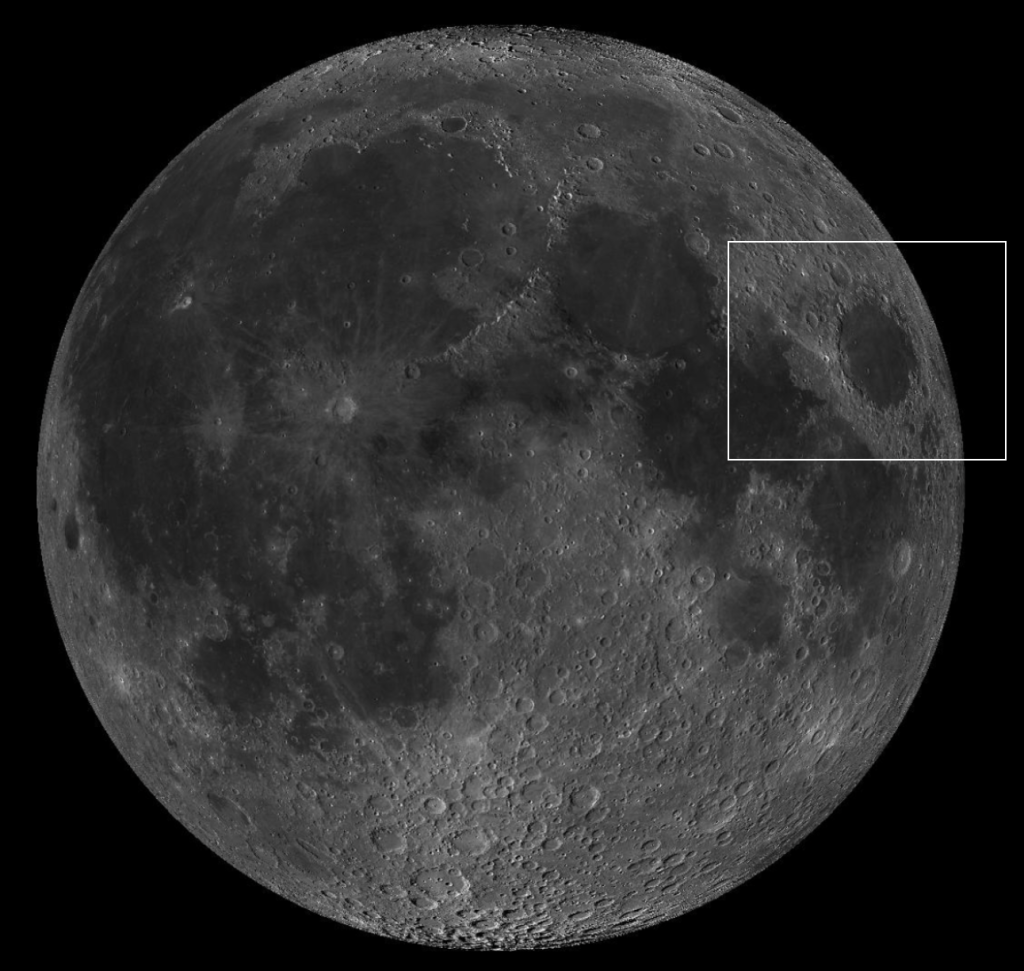

The image below is one further step zoomed out to show the entire region around Mare Crisium, a feature you probably have heard of and one that’s familiar to every lunar observer.

Mare Crisium (“Sea of Crises”) is an easy naked-eye lunar feature located near the eastern limb of the moon. It’s about 550 kilometers in diameter (345 miles) and is the lava-filled remnant of huge asteroid impact.

Just to be thorough, let’s zoom out one more step and look at LROC’s depiction of the entire lunar disk.

Note that LROC’s image of the lunar disk is not just a shot of the full moon. It’s a composite of tens of thousands of individual shots from LROC’s wide and narrow-angle cameras. You can see topography and detail across the width of the lunar disk because all the images where chosen from examples with shadow relief similar to what a telescopic observer sees when observing near the lunar sunlight terminator.

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has been orbiting the moon since 2009 and is one of those NASA missions that just continues to quietly do its thing without much fanfare or glitz. But for amateur astronomers who love observing the moon, it’s a game-changer.

Along with the fantastic imagary and almost limitless zoom capablities, the LROC QuickMap has a bewildering selection of image overlays containing much more detail and technical content. My favorite is the simple “nomenclature” checkbox which turns on common labels for thousands of features. There’s also a search capability so you can quickly find, for example, less well-known objects (like the crater Proclus!). QuickMap can be an essential tool to aid in your lunar observing, or a full-on substitute for those who aren’t able to get out with the telescope as often as they’d like.

All of the imagery in the QuickMap tool is from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera suite, which contains two narrow angle cameras and a single wide angle camera. The cameras are all built by Malin Space Science Systems and run by teams of scientists centered largely around Arizona State University in Tempe, but including team members from countless other institutions. The combo of Malin Systems and Arizona State are also responsible for the HIRISE camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Together, they are arguably among the most sophisticated cameras ever built for any purpose.

I’ve spent literal hours playing with LROC QuickMap. I pull it out when I’m reading something about the moon and want to look at additional imagery. I always have it open in a browser window when I’m reading Charles Wood’s book or his Sky & Telescope column about the moon. Or when I read anything else about a lunar feature and want to dig deeper. For me, QuickMap is a wonderful rabbit hole and the kind of internet experience that often kills hours and prompts endless further questions and explorations.

Take a look and have fun!

(post by John Rummel, August, 2025)